Introduction

Looking back on my first year in the journalism program, I realize that many of the things that I saw to be typical practices were not at all normal. That year and the year to follow, basically every "big" article was subject to prior review, and because this happened every month, I just took it as the way things happened. When we submitted FOIA requests we were looked down upon by administrators. After attending journalism conventions my sophomore and junior years, I became much more educated on my rights and as a student journalist, and began to realize the implications that constant and unnecessary prior review was having on the work of myself and my staff. Every member of the staff was guilty of self-censorship in someway due to the overbearing hand of principal using prior review to control our work. My junior year, a situation with censorship from the administration drove us to take a stand for our rights and, unfortunately, that is still a fight that continues to today. I used the censorship to fuel my drive to bring about change and helped with the passage of the Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act, a piece of legislation that got rid of the "Hazelwood" standard in Illinois. Below, I have broken down information into three subcategories: Prior review, FOIA requests, and censorship.

Censorship

Background: Last February, a legal disagreement about polls began between the administration and my staff. The administration had just informed teachers about the installation of gender-neutral bathrooms and private PE changing areas that were to take place later in the year. Deeming this newsworthy, I sent out a poll to the student body, asking them about their level of support for these changes.

Several days after the poll was sent out, local conservative websites posted articles about the gender-neutral bathrooms and featured screenshots of my poll. A day or so after the local posts about the matter, I realized that there were errors with the survey (people could submit multiple responses) and decided to close the poll. After creating an updated version, I was directed by administrators to not send out the updated poll because my action was pending investigation to see if I was in violation of a school board policy regarding student privacy. After over a week with no decision made about the violation. The staff decided that we needed to contact SPLC and also write about the situation in the coming issue of the paper.

The editorial that I wrote addressed prior review, censorship and the importance of the "New Voices" bill that was, at the time, in the Illinois legislature. This editorial was circulated throughout the state, widely read and used to spread awareness to congressmen, and everyone else, about the importance of a free student press. Because of this editorial and the timing of our legal issues, I was asked to speak at the bill's committee hearing in the Illinois legislature. I had to decline, sadly, because of AP tests I had on that day. However, I still felt compelled to share our story of censorship and the importance of the "New Voices" campaign. At the 2016 JEA/NSPA journalism convention in Indianapolis, my fellow editor-in-chief and I presented on our experiences. This was an amazing opportunity for us to use our experience to help others.

The editorial that I wrote addressed prior review, censorship and the importance of the "New Voices" bill that was, at the time, in the Illinois legislature. This editorial was circulated throughout the state, widely read and used to spread awareness to congressmen, and everyone else, about the importance of a free student press. Because of this editorial and the timing of our legal issues, I was asked to speak at the bill's committee hearing in the Illinois legislature. I had to decline, sadly, because of AP tests I had on that day. However, I still felt compelled to share our story of censorship and the importance of the "New Voices" campaign. At the 2016 JEA/NSPA journalism convention in Indianapolis, my fellow editor-in-chief and I presented on our experiences. This was an amazing opportunity for us to use our experience to help others.

Prior Review

In my college recommendation letter, my adviser jokes about me having the "dubious honor" of the most articles submitted for prior review out of all the editors she has had in her 19 year career. Along with writing the editorial about prior review and censorship, my fellow editor-in-chief and myself also decided that we should start informing our readers when stories went through the prior review process by printing a note at the bottom of the article. Ironically, the editorial where we talk about this note was submitted for prior review and therefore has a note at the bottom.

Story:

Just as an entrepreneurship class teaches students the ins and outs of the business world and an art class equips artists with techniques that will help them create a career out of their talent, a high school journalism program educates students by teaching them the skills that are practiced by professionals. The fundamental principles of journalism aren’t just meant to be taught, they’re meant to be practiced, and practiced without the fear of interference from outside bodies.

This being said, The Omega will never be able to properly inform the school community, give a voice to students, or practice sound journalism with the increasing burden of prior review and censorship that has occurred in recent months.

The Supreme Court case that limits the rights of student press, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, is confusing to say the least. The language of the decision leaves a lot of things open to interpretation and has been the heart of The Omega’s recent problems. This confusion over what rights administrators have is what has most likely led to the dramatic increase of journalistic restraint from administrators across the nation.

Recently proposed Illinois House bill 5902, also known as the Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act, would improve this situation. Not only does this bill protect students’ rights to exercise freedom of speech and press, it also secures for students the right to determine what is the content of the publication.

All that we have to say about this bill is this: it’s about time.

Even under the Hazelwood standard, some administrators show more regard for students’ expression rights than others. Just because administrators have the right to invoke prior review, doesn’t mean they necessarily should.

Excessive administrative involvement in the editorial process creates both an adversarial relationship between the student press and administration and self-censorship by the student journalists. Our coverage of school policies and events this year, such as the proposed Master Facility Plan, the different aspects of Red Ribbon Week and more recently the gender-neutral spaces, has received an unprecedented amount of prior review and censorship.

Between the fall of 1999 and spring of 2011, The Omega received a total of three requests for prior review from administration. Last year, six articles were subject to prior review. So far this year, eight articles have been reviewed by administration before being published.

When administrators make changes to school policy articles before they are published, it is a conflict of interest. In the majority of cases, it is against professional journalistic ethics to allow a person or group to preview an article about themselves before it is published. If we aren’t going to allow a sports team or any other person to make changes on an article about themselves, administrators should expect the same.

We have a responsibility to readers to practice sound journalism by writing truthfully about topics that are important to our audience: the student body.

Earlier this month, one of our editors-in-chief emailed a two-question survey asking about the student body’s views regarding proposed gender-neutral spaces. Finding two minor errors in the survey (slightly misleading wording of one of the questions and a problem with how the survey was set up that allowed users to send multiple responses and skew results), the editor planned on re-sending an updated version but was told by administrators to refrain from doing so because of a pending investigation into whether or not the survey violated board policy 7.15.

Due to the fact that we did not receive an explanation for the restraint or a final decision on the investigation until more than a week later, (requiring us to push our publication back more than a week as well) the Omega considered this an act of unlawful censorship. According to administration, the survey was not considered appropriate for all students.

However, the two questions on the survey only included information that was given to The Omega by the administration.

In December, during the review of an article regarding the proposed Master Facility Plan renovations, administration requested for the reporter to change quotes said by a faculty member to ones that diluted the meaning of the original. The Omega contacted outside counsel and fought to publish the original quotes.

The best way for administration to confront problems they might have with a school publication’s content is through letters to the editor and asking for corrections to be published in a later issue. This allows students to still report freely without administrative involvement but still gives the school the ability to voice any legitimate concerns they may have.

Despite all our criticism of administrative involvement, we get where they are coming from. There is an understandable anxiety that comes with the possibility of a student newspaper embarrassing a school or administrator, but ultimately, there has got to be a little faith that student journalists will follow their own high ethical standards.

Having a relationship with administration where there is a constant fear of unnecessary involvement leads student journalists to self-censor themselves, unconsciously taking away some of their own freedom of speech because of the fear of administrative backlash. But if the student press doesn’t say it, who else will?

According to a survey conducted by the Brookings Institution, a mere 1.4 percent of news media coverage is devoted to education. If student journalists do not cover decisions and policy changes throughout the district, these important topics risk going unreported, also risking the possibility that the sole information about said topics is uneducated online gossip.

There is a need in every school for a well-educated student press to set the record straight and be able to do legitimate reporting, have a reasoned opinion, and promote a more informed community. We have a crucial role in the marketplace of ideas and censoring does nobody any favors.

In light of this, the Omega has decided that it is our obligation as journalists to inform our readers when these acts of prior review occur. As of this issue, all articles that have gone through the prior review process will be printed with an editor’s note, noting this fact.

The Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act isn’t just something that we want, it is something that we need. In order for our rights to be secured and to do the best reporting possible, censorship cannot be a thing. As high school students negatively affected by acts of prior review and censorship, we know that our rights have been compromised.

We need them back.

Published: Online at dgnomega.org and in print on March 24, 2016.

Just as an entrepreneurship class teaches students the ins and outs of the business world and an art class equips artists with techniques that will help them create a career out of their talent, a high school journalism program educates students by teaching them the skills that are practiced by professionals. The fundamental principles of journalism aren’t just meant to be taught, they’re meant to be practiced, and practiced without the fear of interference from outside bodies.

This being said, The Omega will never be able to properly inform the school community, give a voice to students, or practice sound journalism with the increasing burden of prior review and censorship that has occurred in recent months.

The Supreme Court case that limits the rights of student press, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, is confusing to say the least. The language of the decision leaves a lot of things open to interpretation and has been the heart of The Omega’s recent problems. This confusion over what rights administrators have is what has most likely led to the dramatic increase of journalistic restraint from administrators across the nation.

Recently proposed Illinois House bill 5902, also known as the Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act, would improve this situation. Not only does this bill protect students’ rights to exercise freedom of speech and press, it also secures for students the right to determine what is the content of the publication.

All that we have to say about this bill is this: it’s about time.

Even under the Hazelwood standard, some administrators show more regard for students’ expression rights than others. Just because administrators have the right to invoke prior review, doesn’t mean they necessarily should.

Excessive administrative involvement in the editorial process creates both an adversarial relationship between the student press and administration and self-censorship by the student journalists. Our coverage of school policies and events this year, such as the proposed Master Facility Plan, the different aspects of Red Ribbon Week and more recently the gender-neutral spaces, has received an unprecedented amount of prior review and censorship.

Between the fall of 1999 and spring of 2011, The Omega received a total of three requests for prior review from administration. Last year, six articles were subject to prior review. So far this year, eight articles have been reviewed by administration before being published.

When administrators make changes to school policy articles before they are published, it is a conflict of interest. In the majority of cases, it is against professional journalistic ethics to allow a person or group to preview an article about themselves before it is published. If we aren’t going to allow a sports team or any other person to make changes on an article about themselves, administrators should expect the same.

We have a responsibility to readers to practice sound journalism by writing truthfully about topics that are important to our audience: the student body.

Earlier this month, one of our editors-in-chief emailed a two-question survey asking about the student body’s views regarding proposed gender-neutral spaces. Finding two minor errors in the survey (slightly misleading wording of one of the questions and a problem with how the survey was set up that allowed users to send multiple responses and skew results), the editor planned on re-sending an updated version but was told by administrators to refrain from doing so because of a pending investigation into whether or not the survey violated board policy 7.15.

Due to the fact that we did not receive an explanation for the restraint or a final decision on the investigation until more than a week later, (requiring us to push our publication back more than a week as well) the Omega considered this an act of unlawful censorship. According to administration, the survey was not considered appropriate for all students.

However, the two questions on the survey only included information that was given to The Omega by the administration.

In December, during the review of an article regarding the proposed Master Facility Plan renovations, administration requested for the reporter to change quotes said by a faculty member to ones that diluted the meaning of the original. The Omega contacted outside counsel and fought to publish the original quotes.

The best way for administration to confront problems they might have with a school publication’s content is through letters to the editor and asking for corrections to be published in a later issue. This allows students to still report freely without administrative involvement but still gives the school the ability to voice any legitimate concerns they may have.

Despite all our criticism of administrative involvement, we get where they are coming from. There is an understandable anxiety that comes with the possibility of a student newspaper embarrassing a school or administrator, but ultimately, there has got to be a little faith that student journalists will follow their own high ethical standards.

Having a relationship with administration where there is a constant fear of unnecessary involvement leads student journalists to self-censor themselves, unconsciously taking away some of their own freedom of speech because of the fear of administrative backlash. But if the student press doesn’t say it, who else will?

According to a survey conducted by the Brookings Institution, a mere 1.4 percent of news media coverage is devoted to education. If student journalists do not cover decisions and policy changes throughout the district, these important topics risk going unreported, also risking the possibility that the sole information about said topics is uneducated online gossip.

There is a need in every school for a well-educated student press to set the record straight and be able to do legitimate reporting, have a reasoned opinion, and promote a more informed community. We have a crucial role in the marketplace of ideas and censoring does nobody any favors.

In light of this, the Omega has decided that it is our obligation as journalists to inform our readers when these acts of prior review occur. As of this issue, all articles that have gone through the prior review process will be printed with an editor’s note, noting this fact.

The Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act isn’t just something that we want, it is something that we need. In order for our rights to be secured and to do the best reporting possible, censorship cannot be a thing. As high school students negatively affected by acts of prior review and censorship, we know that our rights have been compromised.

We need them back.

Published: Online at dgnomega.org and in print on March 24, 2016.

FOIA requests

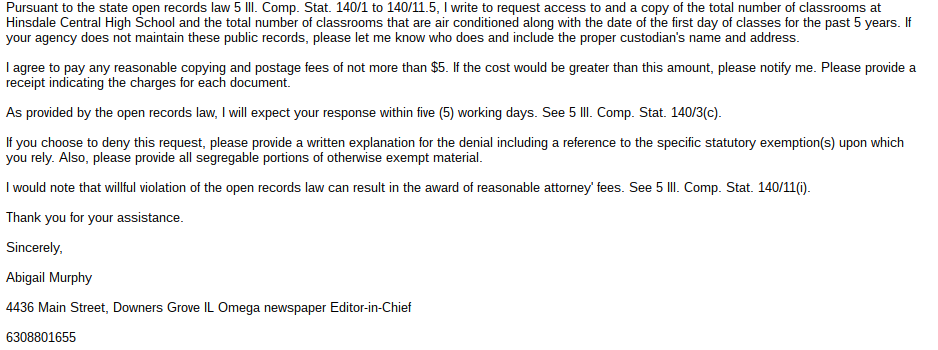

About: Over the last two years, I have submitted eight FOIA requests for various articles. The first time I had to use FOIA to get information was while writing my article about a Red Ribbon Week speaker (see article here). For the Red Ribbon Week campaign, the school used data from the Illinois Youth Survey, a statewide survey that the school takes every other year. After spending almost two weeks trying to convince administrators to give me the survey in its entirety, I decided to use a FOIA request to obtain the information. Although administrators were not pleased with my decision to use this route to obtain the survey, I knew that it was the only way I was going to be able to get the information in time to include it in my survey. Learning more about FOIA in order to send the request for this story made me more educated on my rights. I did research online to find out more about FOIA and used SPLC's FOIA request generator to create the letters I sent out. An example of a FOIA request I sent for my story on the 2017-2018 calendar change appears below (see article here).